Since the Industrial Revolution, the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide has increased – almost 50% – from 280 to over 400 parts per million. This increase is from human activities like the burning of fossil fuels such as coal, gas, and oil, along with land-use change.

Ocean acidification (OA) refers to a change in ocean chemistry in response to the uptake of increasing carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere.

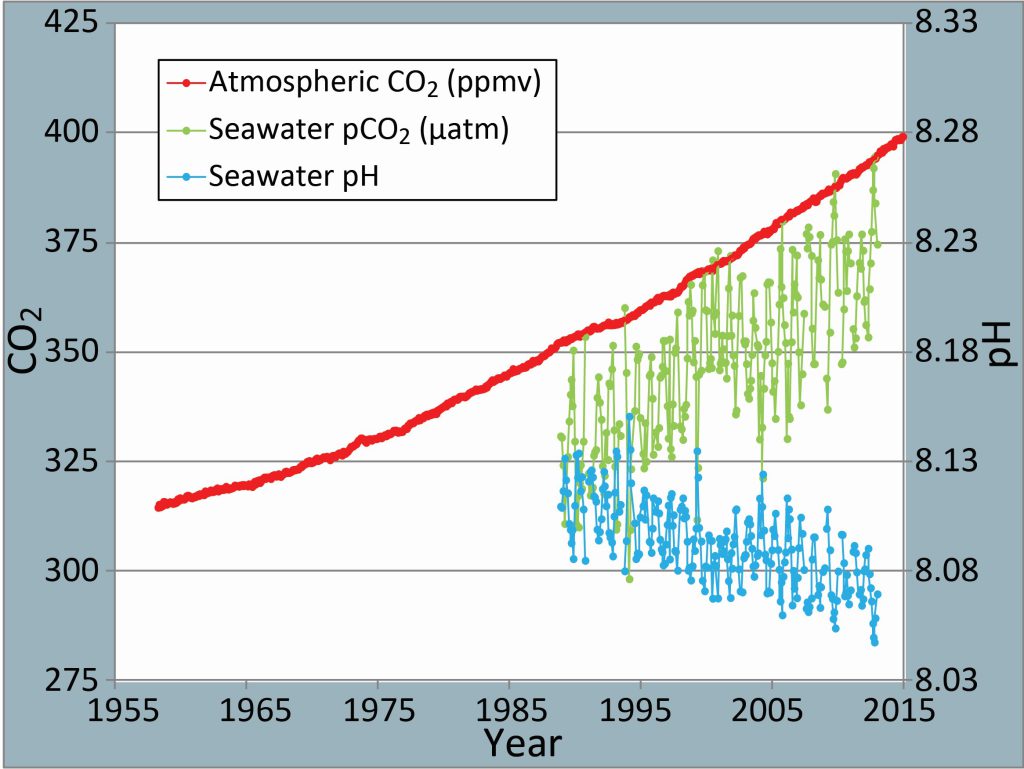

Increases in carbon dioxide (known as CO2) in the atmosphere drive corresponding increases in dissolved CO2 within the surface waters of our ocean. This dissolved CO2 reacts with seawater to form carbonic acid (H2CO3). Carbonic acid breaks apart to form bicarbonate ions (HCO3 – ) and hydrogen ions (H + ). Hydrogen ions (H + ) act like free agents. And while the ocean is not acidic, these free agent hydrogen ions cause the seawater to become more acidic. We measure this using pH (H represents hydrogen ions). The free agent hydrogen ions also react with carbonate ions (CO3 2- ) to form bicarbonate (HCO3 – ), making carbonate ions relatively less abundant. Next, find out why this matters next.

This is how carbonate ions help to buffer seawater against large changes in pH by reacting with some of the excess hydrogen ions and forming bicarbonate. However, carbonate ions (CO3 2- ) are an important part of calcium carbonate (CaCO3).

Learn about what we measure, and why. Download the infographic for even more.

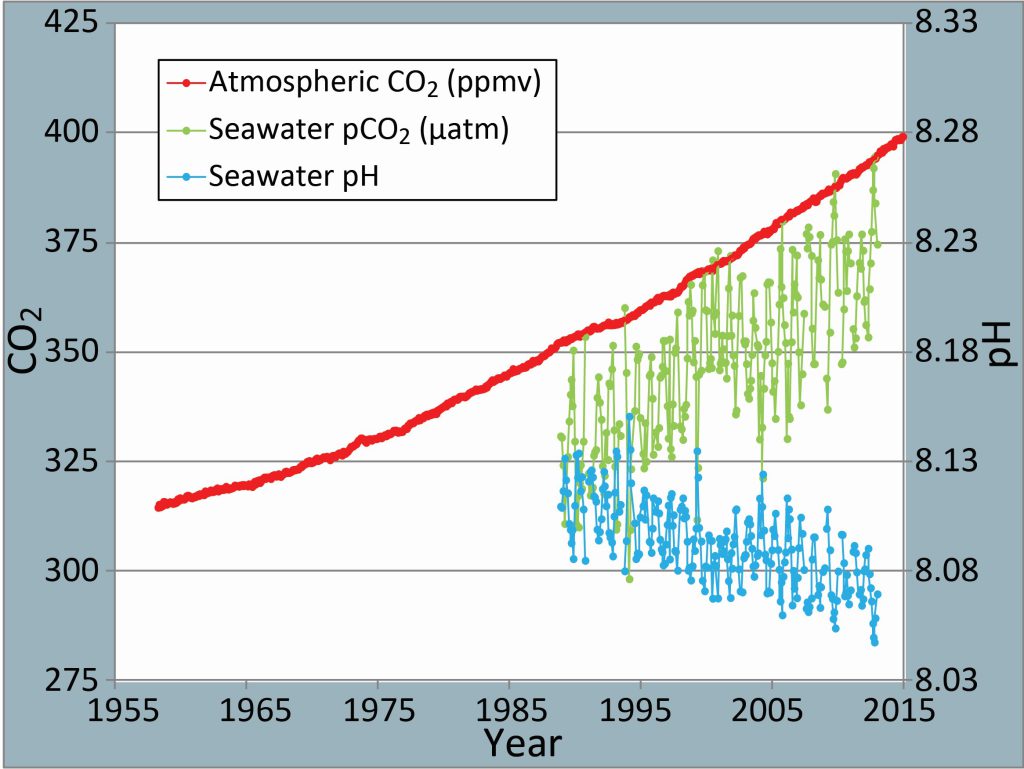

When the ocean absorbs carbon dioxide, chemical reactions create hydrogen ions that act like free agents, able to react with other compounds. Two ways we track ocean acidification are through pH and total alkalinity (TA). pH is a measure of how many free hydrogen ions are in the seawater. The more carbon dioxide in the ocean, the more these free agents are created, causing lower pH (more acidic).

The partial pressure of CO2 (pCO2) tells us how much carbon dioxide is in seawater. This information helps us understand ocean carbonate chemistry and biological productivity in the region. pCO2 increases when the ocean absorbs more CO2 from the atmosphere with elevated emissions.

Alkalinity is the ocean’s buffering system against increasing acidity. Total alkalinity is a measure of the concentration of buffering molecules like carbonate and bicarbonate in the seawater that can neutralize acid.

Dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) tells us how much non-biological carbon is in seawater. Inorganic carbon comes in three main forms that we measure for DIC: carbon dioxide ( CO2), bicarbonate (HCO3 - ), and carbonate (CO3 2- ). Understanding DIC can help us determine the balance of carbonate forms in the ocean and the likelihood of ocean acidification.

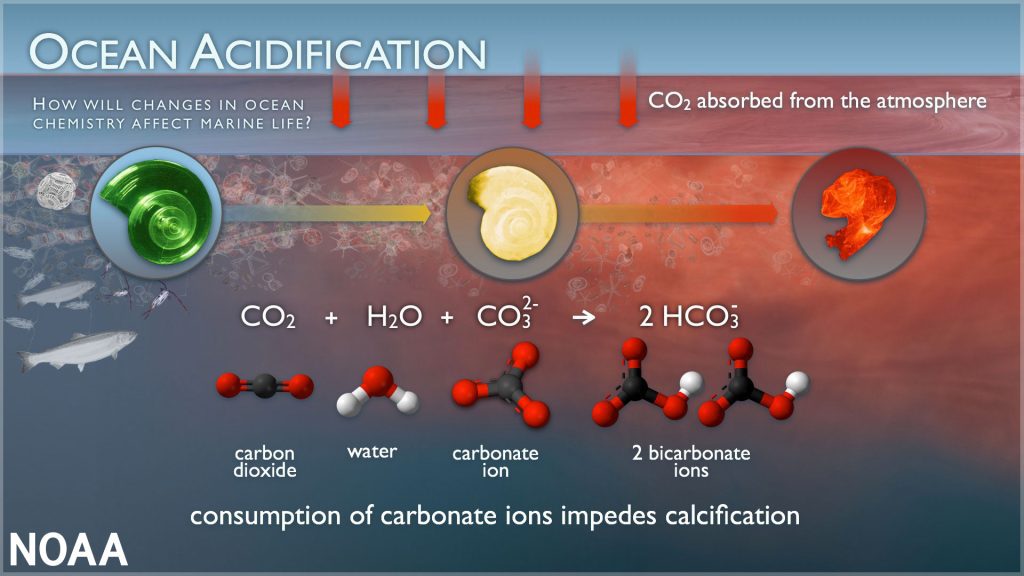

Local coastal processes can cause acidification.

Coastal acidification includes local changes in water chemistry that can arise from human inputs on land as well as natural processes.

Coastal upwelling is a natural process that brings deeper,

more acidic waters to the surface ocean in the coastal zone. Upwelling occurs primarily

on the western boundaries of continents, but the timing, duration and severity of upwelling events may increase with climate change.

Human impacts include excess nutrient run-off (e.g. nitrogen and organic carbon) from land. This runoff can cause increases in algal growth, commonly known as ‘blooms’. When these algal blooms die, they consume oxygen and release carbon dioxide and increasing acidity.

Coastal acidification can also occur with changes in water column circulation occur. Changes in wind, temperature, or salinity changes can have both natural and human causes.

The impacts of ocean acidification depend on the timing, duration, and severity of acidification, how marine life and ecosystems respond, and the effects on people who depend on healthy coastal ecosystems.

Freshwater bodies like the Great Lakes also experience acidification. Researchers project that pH, the measure of how acidic or alkaline the water body is, will decline at a rate similar to that of the oceans in response to increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide.

Absorption of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere isn’t the only source of acidification. The Great Lakes are also recovering from acid deposition. The Midwestern and Northeastern United States experienced an increase in deposition of sulfuric and nitric acids from the early 20th century until air-quality regulations mitigated this trend.

Present-day mean pH and alkalinity vary according to the geology of each lake basin, with Superior having the most acidified waters and Michigan the least acidified. In addition, considerable short-term spatial and temporal variability in pH occurs, driven largely by varying rates of photosynthesis, respiration, and seasonal mixing. There has not been any long-term robust monitoring of acidification in the Great Lakes system until recently.

What’s at stake from ocean acidification may be different depending on where you live. As a community member, you can take a larger role in educating the public about ocean acidification.

There are many actions you can take to reduce your personal carbon footprint. From helping to reduce oil consumption with petrol products to making your home more energy efficient.

The NOAA Ocean Acidification Program (OAP) works to build knowledge about how to adapt to the consequences of ocean acidification and conserve marine ecosystems as acidification occurs.